- College Inside

- Posts

- Parole boards say education matters. Their denials tell a different story.

Parole boards say education matters. Their denials tell a different story.

A new analysis from the Prison Policy Initiative finds that while education is supposed to help demonstrate readiness for release, parole boards often treat it as a box to check—or a reason to say no.

A biweekly newsletter about higher education during and after incarceration. Written by Open Campus national reporter Charlotte West.

A 2024 college graduation at Sing Sing Correctional Facility in New York. Photo by Babita Patel for Open Campus.

After 24 years in prison, a 58-year-old woman went before California’s parole board for the first time with what looked like a strong case for release. She had earned an associate’s degree and was working toward a bachelor’s at Cal State LA. She had completed years of programming, earned praise from correctional staff, and hadn’t had a violent disciplinary infraction in more than two decades.

At a hearing in the fall of 2023, a parole commissioner started with some good news: "You've done everything objectively speaking that we want you to do." Unfortunately, there was a problem: "the subjective part of you hasn't quite gotten to the surface that you've addressed it to the depth that you need to." Figuring out exactly what those words meant was confusing, but the final decision was clear. The board denied her parole.

The exchange reflected a conundrum familiar to many incarcerated people seeking release—meeting every official requirement isn’t always enough when decisions hinge on something much harder to pin down.

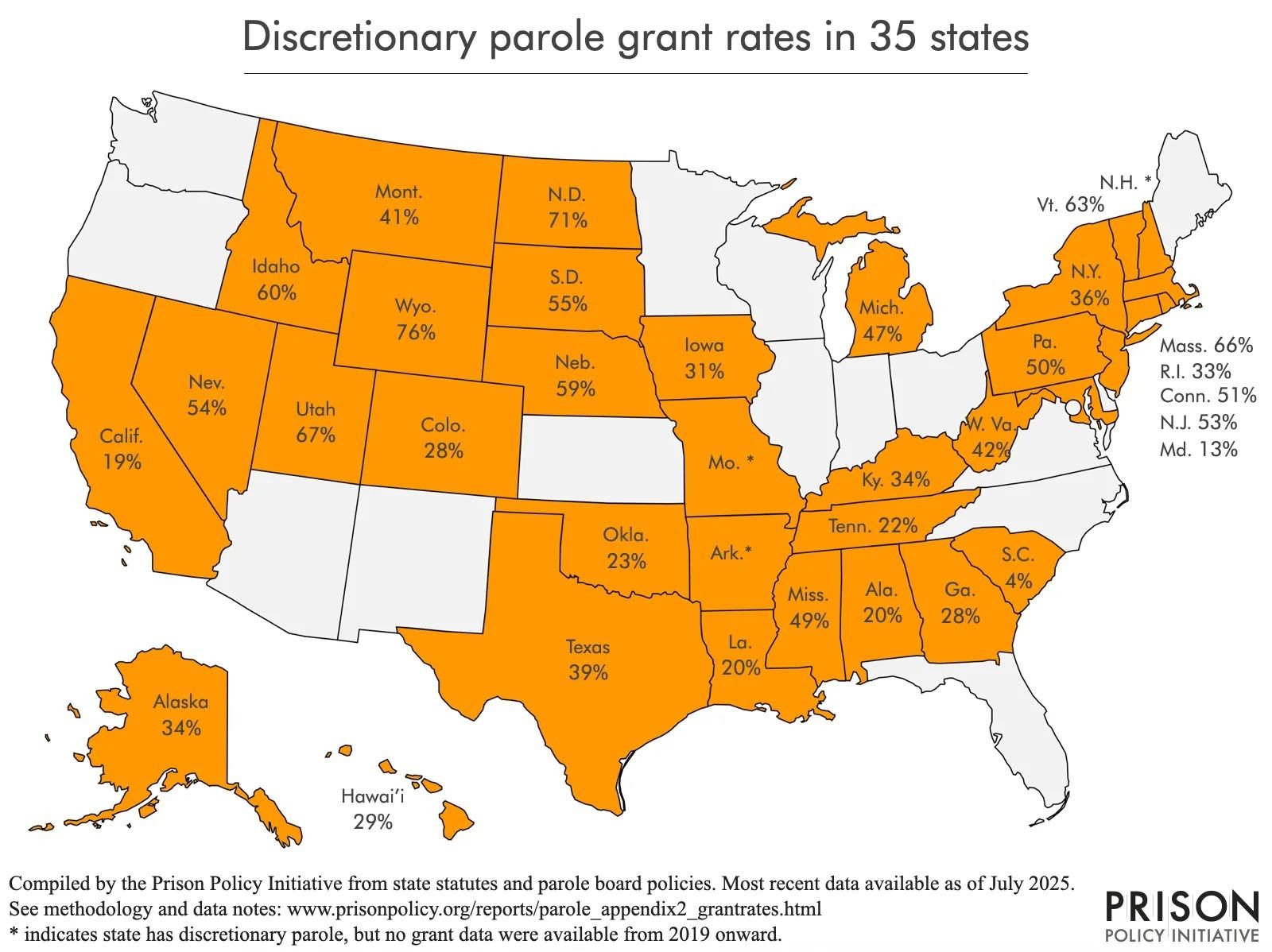

California is one of 35 states that allow people to appear before a parole board, which decides whether they should be released before their sentence ends based on factors such as conduct, rehabilitation, and perceived risk. California granted parole in only about one in five cases in 2024, according to the nonprofit Prison Policy Initiative, or PPI.

The California woman’s case echoes findings from a new two-part analysis by the organization examining how parole boards operate. The remaining states have effectively eliminated parole altogether—a trend that continued in 2024 when Louisiana became the 17th state to abolish it.

Image courtesy of the Prison Policy Initiative.

The report describes a parole system that’s politically motivated, under-resourced, and often dysfunctional—with declining approval rates and fewer hearings despite a national backlog of more than 200,000 people incarcerated past their parole-eligibility dates. The PPI report finds that those problems are especially apparent in how parole boards weigh education and other programming—achievements often framed as a sign of transformation but very often dismissed or ignored. While states such as Massachusetts and Pennsylvania explicitly direct boards to consider an individual’s educational or vocational progress, the report shows that in practice these achievements rarely outweigh other factors.

About half of the 35 states list education as a forward-looking factor in release decisions, but the reality is more complicated. The report finds that even though educational accomplishments can help someone's case, they are often dismissed as insufficient—or even used as negative strikes if applicants are unable to complete them.

“Parole statutes pay lip service to important dynamic factors, like rehabilitation, preparation, public support, and education, but too often issue denials for static factors, like the original crime, or overly subjective factors, such as the optics of releasing someone who has been convicted of such a crime,” the authors write.

All 35 states require boards to consider the “seriousness” of the crime of conviction, even though judges already weighed that at sentencing. Six states go further, requiring boards to consider whether release would “diminish” respect for the law—a standard focused on optics rather than an individual’s readiness for release, according to the report.

The crime is the one factor people can’t change, yet it often carries the most weight. Degrees, completed programs, and years without disciplinary issues may demonstrate rehabilitation, but they rarely offset the original offense in the eyes of the board.

Image courtesy of the Prison Policy Initiative.

And even the efforts meant to show change can become obstacles. Education and program participation appear frequently in parole guidelines, but the standards can be impossible to meet. The Prison Policy Initiative describes this as a kind of bureaucratic gridlock—parole boards decide the criteria for release, but corrections departments control access to the programs applicants are required to complete. Classes are often canceled, full, or unavailable, leaving people unable to finish what the board requires.

Board members may question these gaps in an applicant’s educational record, even when due to factors beyond the applicant’s control. “Board members may see an incompletion, withdrawal, or other ‘gap’ in an applicant’s record and start to ask questions, even if those changes occurred because of a transfer, illness, or a sincere schedule conflict,” the report notes.

Those contradictions leave many people unsure how to demonstrate readiness for release. A college degree might show a commitment to change, but, as the report suggests, it doesn’t guarantee a fair hearing. “Parole can be denied for nearly any reason at all,” the authors write. “Such denials send a harmful message: the parole board neither recognizes nor rewards transformation.”

Another California transcript shows how boards discount education. In 2022, a man with two associate degrees was denied after 24 years. His programming was neutral, the board said—recent disciplinary infractions proved he lacked real insight into how his programming could help avoid the choices that led him to prison in the first place.

The 58-year-old woman heard similar. Her rehabilitation was "primarily intellectual in nature." Despite her degrees and extensive programming, she hadn't done enough internal work to prevent future harm.

Taken together, the hearings mirror a broader pattern identified by the Prison Policy Initiative report. Educational achievements often become secondary to subjective judgments about whether someone has truly changed. The authors of the report argue that presumptive parole—a system that assumes release once someone has met the state's criteria unless the board provides a specific reason for denial—could move states toward “a fairer framework centered on success and transformation.” They also urge policymakers to focus on measurable signs of change—participation in education, treatment, and work programs—rather than static factors that applicants can never alter.

Read the full PPI report here.

Interested in learning more about the politics of parole? Illinois abolished discretionary parole in 1978, but a handful of people convicted before then remain eligible. Ronnie Carrasquillo was one of them. The PBS documentary "In Their Hands" follows Carrasquillo—who was denied parole more than 30 times despite earning a bachelor's degree in theology and founding education programs in prison—through his decades-long fight for release. The film explores how political pressure and police union influence shape parole board decisions. Watch it here.

Illinois edition of College Inside out now

Last week, Prisoncast! our partner at WBEZ Chicago, sent out the latest print issue of the Illinois edition of College Inside to more than 400 individuals residing in the Illinois Department of Corrections. The issue included an analysis of new data on education waitlists, a story on Augustana College’s recent graduation, a profile of a man who transferred from Illinois to Minnesota to attend law school while still incarcerated, and a round-up of criminal justice news from around the state.

Next, Prisoncast! is teaming up with a group of formerly incarcerated actors and writers to broadcast a new radio play. "The Story of Violence," based on an award-winning script by playwrights at Dixon Correctional Center in Illinois, examines Chicago’s gun violence problem through five characters’ perspectives as their lives intersect at a downtown hotel room. Listen to "The Story of Violence," from WBEZ & Mud Theatre Project, on Thursday, Nov. 6th at 7 p.m. central time on wbez.org.

The 2026-2027 FAFSA for incarcerated students now available

The official 2026-27 FAFSA for incarcerated students is now posted on the NASFAA Prison Education page. Both the English and Spanish versions of the 2026-27 forms are available and ready for use. They are not currently available on the Education Department website due to the government shutdown.

Let’s connect

Please connect if you have story ideas or just want to share your experience with prison education programs as a student or educator. You can always reach me at [email protected] or on Bluesky, LinkedIn, or Instagram. To reach me via snail mail, you can write to: Open Campus, 2460 17th Avenue #1015, Santa Cruz, CA 95062.

We know that not everyone has access to email, so if you’d like to have a print copy College Inside sent to an incarcerated friend or family member, you can sign them up here. We also publish the PDFs of our print newsletter on the Open Campus website.

There is no cost to subscribe to the print edition of College Inside. But as a nonprofit newsroom, we rely on grants and donations to keep bringing you the news about prison education. You can also donate here.

Interested in reaching people who care about higher education in prisons? Get in touch at [email protected] or request our media kit.

Know others that are interested in higher ed in prisons? Let them know about the newsletter. Thanks!

You currently have 0 referrals, only 2 away from receiving a Twitter Shoutout.

Or copy and paste this link to others: https://college-inside.beehiiv.com/subscribe?ref=2p6y6raqDY